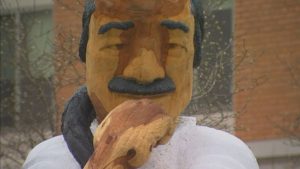

On December 9, 2016, a statue of Leonard Peltier by the artist Rigo 23, was installed on the American University campus in Washington, DC. Beginning this week, a spate of blog posts began to surface—all critical of AU’s exhibition of the statue. The headlines screamed that Leonard Peltier is a “cop killer.” The story was picked up by a FOX news TV channel in DC several days later and today by the Washington Times. The response of the International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee follows.

UPDATE: Due to a media blitz in Washington, DC, by the Federal Bureau of Investigation Agents Association (FBIAA), American University will be moving Rigo 23’s statue of Leonard Peltier. We respect AU’s right to protect its students and property. It should be pointed out, however, that the media blitz launched by the FBIAA created only the illusion that the community (i.e., residents of Washington, DC) was offended by the statue whereas, in reality, only a small segment of that community even had an opinion on the matter.

The FBIAA spokesperson Thomas O’Connor argued that the statue isn’t art, but political speech. True or not, we would remind the FBIAA that political speech is particularly protected under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution… the very Constitution the organization claims to protect.

This is the second time in just over one year that the FBIAA has violated citizens’ right to free speech and expression. In November 2015, members of the same organization interfered with the exhibition of work by the artist Leonard Peltier, an installation that was part of a Native American Month celebration in Washington State.

An innocent man, Leonard Peltier is a Native American activist charged in connection with the deaths of two agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in an incident that took place on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, South Dakota (SD), on June 26, 1975. Government documents show that, without any evidence at all, the FBI decided from the beginning of its investigation to “lock Peltier into the case.”

The Jay Treaty, ratified by the United States and Britain in the 1700s, provides that American Indians dwelling on either side of the boundary line be allowed to cross the U.S.-Canadian border at will. Well after the incident in SD, as he was accustomed to doing, Mr. Peltier legally crossed the border into Canada. At the request of the U.S. government, he was arrested in British Columbia in February 1976. Fearing he wouldn’t receive a fair trial in the U.S., Mr. Peltier applied for asylum. Late in 1976, Mr. Peltier was extradited to the U.S. from Canada.

Mr. Peltier’s extradition to the U.S. was achieved based on false affidavits—obtained by the government through coercion and deceit, and known by the government to be false. The false affidavits had been signed by Myrtle Poor Bear, a Native American woman known to have serious mental health problems.

In the late 1990s, Canada’s Justice Minister Anne McLellan claimed that at Mr. Peltier’s extradition hearings in 1976 no one had lied and that no evidence of fraud existed in the extradition process. She then had the Canadian extradition file sealed for 40 years. Her view is disputed by former Solicitor-General Warren Allmand who had reviewed the case for McLellan’s predecessor Allan Rock. Allmand stated that the extradition ruling was clearly based on the false affidavits (and not on the circumstantial evidence presented, as the U.S. government has claimed), and that extradition would have been denied had the Canadian court known the affidavits were fraudulent. In addition to being a violation of Mr. Peltier’s rights, Mr. Allmand concluded, the U.S. government committed fraud on the Canadian court during the extradition proceedings rendering the extradition illegal.

During oral argument on April 12, 1978, the federal government conceded that, in fact, Myrtle Poor Bear did not know Mr. Peltier, nor was she present at the time of the shooting:

JUDGE ROSS: But anybody who read those affidavits would know that they contradict each other. And why the FBI and Prosecutor’s office continued to extract more to put into the affidavits in hope to get Mr. Peltier back to the United States is beyond my understanding… Because you should have known, and the FBI should have known that you were pressuring the woman to add to her statement.

HULTMAN: Your Honor, I personally was not present at that stage. I read the affidavits after they had been submitted, so I want this court to know that.

JUDGE ROSS: The Government —

HULTMAN: And I don’t excuse, by my remark just now to You Honor, I don’t in any way excuse what the court just indicated. Your Honor, I have trouble with that myself, and Your Honor that is the exact reason which I did read these affidavits and put together the fact that — And that gets to the second point, Judge Gibson and Judge Ross. It was clear to me her story didn’t later check out with anything in the record by any other witness in any other way. So I concluded then, in addition to her incompetence, first, that secondly, there was no relevance of any kind. Absolutely not one scintilla of any evidence of any kind that had anything to do with this case. And it was then that I personally made the decision that this witness was no witness. First of all, because she was incompetent in the utter, utter, utter ultimate sense of incompetency… But, secondly as Judge Ross, you are indicating, and I take no issue at that, Your Honor, but when I then tested those statements once they came to me and that was after they had gone to Canada, and I had a chance to look at them and tested them with all of the record, all of the witnesses, there was not one scintilla that showed Myrtle Poor Bear was there, knew anything, did anything, et cetera.

JUDGE ROSS: But can’t you see, Mr. Hultman, what happened happened in such a way that it gives some credence to the claim of… the Indian people that the United States is willing to resort to any tactic in order to bring somebody back to the United States from Canada… And if they are willing to do that, they must be willing to fabricate other evidence… Was she there at the time?

HULTMAN: No, she was not. I don’t think there is any question on the part of anybody, there is not one scintilla of evidence that indicates, finally, that she is there and has anything to testify to the events.

The Honorable Donald Ross stated in 1978 in conjunction with the 8th Circuit’s United States v. Peltier (585 F.2d 314, 335 n.18):

“The use of the affidavits of Myrtle Poor Bear in the extradition proceedings [of Leonard Peltier from Canada to the U.S.] was, to say the least, a clear abuse of the investigative process by the F.B.I.”

But Mr. Hultman did not tell the truth during oral argument. According to a memorandum by Deputy Assistant Attorney General Robert Kuech dated May 10, 1979, Mr. Hultman (with special prosecutor Robert Sikma), concurred with Canadian Department of Justice attorney Paul William Halprin (who represented the U.S. government in Mr. Peltier’s extradition hearings) that only Myrtle Poor Bear’s second and third affidavit would be used at the extradition hearing—the reason being that the first affidavit was inconsistent with the other two affidavits. In fact, Halprin was responsible for the third affidavit as he requested that certain issues previously provided by Myrtle Poor Bear be amplified. The memo goes on to say that all individuals involved believed Myrtle Poor Bear to be an accurate and reliable witness.

Myrtle Poor Bear confessed she had given false statements after being pressured and terrorized by FBI agents. She sought to testify in this regard at Peltier’s trial. Her father and sister also were expected to testify on Mr. Peltier’s behalf. When Hultman’s former assessment no longer served his purposes, he changed his position entirely. Despite having included Poor Bear on the prosecution’s witness list, Hultman argued that she was an unreliable witness and fought rigorously to prevent her testimony. The judge—without authority or evidence to support his ruling—barred her testimony on grounds of mental incompetence, stating that Poor Bear’s testimony would “shock the conscience of the Court” and the American people.

We note with some interest the recent ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court which found that prosecutors in Georgia violated the U.S. Constitution by striking every black prospective juror in a case against a black defendant (Foster v. Chatman).

In July 1976, Mr. Peltier’s co-defendants Bob Robideau and Dino Butler were acquitted by a Cedar Rapids jury on the grounds of self-defense. Had Mr. Peltier been tried with his co-defendants, he would be a free man today.

For Mr. Peltier’s trial, the government did everything in its power to alter those circumstances which, in its opinion, had materially contributed to the co-defendants’ acquittals—beginning with a change of locale (to Fargo, North Dakota, an area known for its anti-Indian sentiment) and presiding judge. Judge Benson—having a reputation for ruling against Indians and known to have made derogatory extrajudicial references about Mr. Peltier—presided over the trial. In December 1982, defense attorney William Kunstler discovered in a telephone conversation with Judge Edward McManus (presiding judge at the trial of Mr. Peltier’s co-defendants) that McManus, not Benson, had been scheduled to try Mr. Peltier’s case. He had been astonished, he said, to find himself arbitrarily removed in favor of Judge Benson. To this day, it is not clear how McManus’ removal was accomplished or by whom specifically. There appears to have been a concerted effort, however, to prevent the involvement of judges in Mr. Peltier’s trial who had previously made rulings in favor of Indian defendants.

Jury selection, completed in only one day, resulted in an all-white jury despite the presence of a large Native American population in the region. During Mr. Peltier’s trial, it was reported to Judge Benson that one of the jurors had made racist comments. Despite this report and an admission by the juror, the juror was allowed to remain on the jury.

The government presented 15 days of evidence to the jury. The defense planned to present 6 days of evidence. However, due to frequent rulings in the prosecution’s favor, the jury actually heard only 2 and 1/2 days of the defense case.

Mr. Peltier was convicted and sentenced to 2 life terms in prison. He has challenged his conviction in the appellate courts on the basis of over a dozen constitutional violations. See Case of Leonard Peltier: Overview of Constitutional Violations.

During oral argument before the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals in 1985, Judge Gerald Heaney noted the complete lack of evidence of first degree murder in the record. He asked Mr. Crooks, “Just what was Mr. Peltier convicted of?” Mr. Crooks’ declaration during the exchange with Judge Heaney sums up this case:

“Your honor, the government does not know who killed its agents, nor do we know what participation Leonard Peltier may have had in it.”

The lynchpin of the prosecution’s case was the ballistics evidence that the government and the 8th Circuit considered “the strongest evidence” against Mr. Peltier. However, Freedom of Information Act litigation after the trial uncovered exculpatory ballistics reports which had been withheld from Mr. Peltier’s attorneys at trial. An October 2, 1975, teletype was signed off on by ballistics witness Evan Hodge and showed that laboratory tests established that the .223-caliber casing found at the scene of the shoot-out and the AR-15 were not a match. The report concluded that the shell had markings from “a different firing pin than that in [the] rifle used at [the] RESMURS scene.” Further, an October 1, 1975, teletype stated that “none of the ammo” components at the scene could be associated with Peltier’s alleged weapon.

Confronted by the exculpatory ballistics reports which they had withheld from Mr. Peltier’s attorneys at trial, prosecutors retracted the original theory of their case and defended the verdict on a thin “aiding and abetting” theory, to which Judge Heaney replied:

“…this would have been an entirely different case, both in terms of the manner in which it was presented to the jury and the sentence that the judge imposed, if the only evidence that you have was that Leonard Peltier was participating on the periphery in the fire fight and the agents got killed. Now that would have been an entirely different case… I don’t think this would have been the same case at all. We could have resolved this issue without great difficulty if the government had presented the case against Peltier on the theory that he was an aider and abettor… But this is not the government’s theory. Its theory, accepted by the jury and the judge, was that Peltier killed the two FBI agents at point-blank range with the Wichita AR-15. Under this theory, the ballistics evidence, particularly as that evidence relates to a.223 shell casing, allegedly extracted from the Wichita AR-15 and found in agent Coler’s car, is critical.”

The court noted that: “The record as a whole leaves no doubt that the jury accepted the government’s theory that Peltier had personally killed the two agents, after they were seriously wounded, by shooting them at point blank range with an AR-15 rifle (identified at trial as the Wichita AR-15).”

The Circuit Court implicitly acknowledged that the government had used dishonest means to effect Peltier’s conviction. The court concluded that the government:

“…withheld evidence from the defense favorable to Peltier,” which “cast a strong doubt on the government’s case,” and that had this other evidence been brought forth, “there is a possibility that a jury would have acquitted Leonard Peltier.”

Indeed, when questioned by a private investigator after the trial, a juror said that if the jury had known about the exculpatory ballistics reports they never would have found Leonard Peltier guilty as charged.

The court further found there was more than one AR-15 in the area at the time of the shoot-out.

Mr. Peltier’s conviction was upheld, however, based on the court’s strict interpretation of the Bagley standard (United States v. Bagley, 478 U.S. 667, 1985). Judge Gerald Heaney later commented that, under the circumstances, a jury might well have arrived at a different decision, but said these circumstances fell short of the judicial standard required in ordering a new trial, i.e., the court must find that the jury “probably” rather than “possibly” would have acquitted Leonard Peltier. It was, he said, “the toughest decision I ever had to make in twenty-two years on the bench.”

On November 9, 1992, again during oral argument before the U.S. Court of Appeal for the 8th Circuit, the government repeatedly admitted in unequivocal language that it did not prove and disclaimed the ability to prove that Mr. Peltier was the person who shot the agents at close range. The government conceded that the evidence was “sketchy” on the subject of who actually shot the FBI agents. Mr. Crooks stated:

“The case was basically tried with the assumption that we would maybe not convince all those jurors that he was the one that pulled the trigger down by the bodies. Because as I’ve outlined in my brief the evidence is sketchy—even with that shell casing the evidence is sketchy on that subject.”

Upon further questioning by Senior Circuit Judge Friedman, Mr. Crooks stated:

“We had a murder. We had numerous shooters… But we did not know, quote unquote, who shot the agents.”

In 2003, Judges Seymour, Anderson and Brorby issued this statement in conjunction with the 10th Circuit’s Peltier v. Booker (348 F.3d 888, 896):

“Much of the government’s behavior at the Pine Ridge Reservation and in its prosecution of Mr. Peltier is to be condemned. The government withheld evidence. It intimidated witnesses. These facts are not disputed.”

In an April 18, 1991, letter to Senator Daniel Inouye, Chair of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs (a long-time Peltier advocate), Senior 8th Circuit Judge Gerald Heaney wrote:

“The FBI used improper tactics in securing Peltier’s extradition from Canada and in otherwise investigating and trying the Peltier case. Although our court decided that these actions were not grounds for reversal, they are, in my view, factors that merit consideration in any petition for leniency filed… We as a nation must treat Native Americans more fairly… Favorable action by the President in the Leonard Peltier case would be an important step in this regard.”

On May 21, 1992, Minneapolis Special Agent in Charge Nicholas V. O’Hara met with Judge Heaney to “voice his professional concerns and those of FBI agents Bureau-wide concerning Judge Heaney’s letter to Senator Inouye…” and to dissuade him from supporting the release of Leonard Peltier. “The substance of the discussion with Judge Heaney centered on the fact that Peltier supporters and sympathizers were capitalizing on his letter of April 18, 1991, to generate emotion, support and sympathy which could ultimately lead to the early release of Leonard Peltier.” The visit by the FBI to Judge Heaney did not have the desired effect. On October 24, 2000, in a letter to Senator Inouye, Heaney stated: “I have reviewed my letter to you of April 18, 1991, and adhere to the views I expressed therein.” Subsequent to reaching out to Judge Heaney, the FBI, on February 16, 1993, developed a plan to prevent Peltier’s release, a strategy with an emphasis on media manipulation.

Eligible since 1986, Peltier is long overdue for parole. The US Parole Commission has yielded to the objections of the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice in denying Peltier’s applications for parole at every turn—most recently in 2009 when he was told he will not receive another full parole hearing until 2024 when, if he survives, he will have reached nearly the age of 80 years.

From the time of Peltier’s conviction in 1977 until the mid-1990s—according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice—the average length of imprisonment served for homicide in the United States ranged from 94 to 99.8 months (about 8 years) prior to being released on parole. Mr. Peltier has the right to equal justice, i.e., application of the existing standards at the time of his conviction. Even if you were to take Peltier’s two consecutive life sentences into account, it is clear that Peltier should have been released a long time ago. Instead, according to 1977 standards, he has served the equivalent of over five life sentences.

Further, in determining his release date, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) also has failed to take into account Mr. Peltier’s time in prison prior to his conviction in 1977 (over one year), as well as the good-time credit (20 years total, to date) earned. Instead, the BOP has consistently stated that Mr. Peltier presumptive release date is October 11, 2040.

As mentioned previously, Senator Inouye (deceased) was an ardent supporter of Mr. Peltier, but he was only one of over 55 Members of Congress who have supported Mr. Peltier over the past 40 years.

In 2000, for example, the Honorable Don Edwards (D-CA, Retired), a former FBI agent himself and Chairman of the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights in the U.S. House of Representatives for 23 years, stated:

“I took a personal interest in Mr. Peltier’s case and became convinced that he never received a fair trial. Even the government now admits that the theory it presented against Mr. Peltier at trial was not true… Leonard Peltier has served an inordinate amount of time and deserves the right to consideration of his clemency request [under consideration by then president Bill Clinton] on the facts and the merits. The FBI continues to deny its improper conduct on Pine Ridge during the 1970’s and in the trial of Leonard Peltier. The FBI used Mr. Peltier as a scapegoat and they continue to do so today. At every step of the way, FBI agents and leadership have opposed any admission of wrongdoing by the government, and they have sought to misrepresent and politicize the meaning of clemency for Leonard Peltier. The killing of FBI agents at Pine Ridge was reprehensible, but the government now admits that it cannot prove that Mr. Peltier killed the agents.”

The case of Leonard Peltier is a lengthy and complicated one. Media owes it to the public to thoroughly investigate the case before printing scurrilous claims and using sensationalistic headlines.

More information on the Peltier case is available at www.whoisleonardpeltier.info.

Don’t let false reports on the Peltier case go unanswered. Write your comments here:

https://www.campusreform.org/?ID=8567

http://m.washingtontimes.com/news/2016/dec/28/leonard-peltier-cop-killer-statue-at-american-univ/

http://www.fox5dc.com/news/local-news/225636036-story

http://breakingnewslive.net/news/leonard-peltier-cop-killer-statue-at-american-university-installed-in-plea-for-obama-pardon?uid=134412

http://latestnewsheadlines.ddns.net/news/leonard-peltier-cop-killer-statue-at-american-university-installed-in-plea-for-obama-pardon

http://www.cnsnews.com/news/article/barbara-hollingsworth/